Clojure Support for Popular Data Tools: A Data Engineer's Perspective, and a New Clojure API for Snowflake

In this article I look at the extent of Clojure support for some popular on-cluster data processing tools that Clojure users might need for their data engineering or data science tasks. Then for Snowflake in particular I go further and present a new Clojure API.

Why is the level of Clojure support important? As an example, consider that Scicloj is mostly focused on cases where your data fits on a single machine. As such, if you need to work with a large dataset it will be necessary to compute on-cluster and extract a smaller result before continuing your data science task locally.

However, without sufficient Clojure support for on-cluster processing, anyone needing that facility for their data science or data engineering task would be forced to reach outside the Clojure ecosystem. That adds complexity in terms of interop, compatibility and overall stack requirements.

With that in mind, let's examine the level of Clojure support for some popular on-cluster data processing tools. For each tool I selected its official Clojure library if one exists, or if not the most popular and well-known community-supported alternative with at least 100 stars and 10 contributors on GitHub. I then used the following criteria against the library to classify it as "supported" or "support unknown":

- CI/CD build passing

- Most recent commit less than 12 months ago

- Most recent release less than 12 months ago

- Maintainers responded to any issue or question less than 12 months ago

- Maintainers either accepted or rejected any PR less than 12 months ago

If I couldn't find any such library at all, I classified it as having "no support".

| Tool Category | Supported | Support Unknown | No Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| On-cluster batch processing | 1. Spark (see Spark Interop with Geni below) | ||

| On-cluster stream processing | 2. Kafka Streams (see Kafka Interop with Jackdaw below) | 3. Spark Structured Streaming, 4. Flink | |

| On-cluster batch and stream processing | 5. Databricks (see Spark Interop with Geni below), 6. Snowflake (see Snowflake Interop below) |

Please note, I don't wish to make any critical judgments based on either the summary analysis above or the more detailed analysis below. The goal is to understand the situation with respect to Clojure support and highlight any gaps, although I suppose I am also inadvertently highlighting the difficulties of maintaining open source software!

Spark Interop with Geni

Geni is the go-to library for Spark interop. Some months back, I was motivated to evaluate the coverage of Spark features. In particular, I wanted to understand what would be involved to support Spark Connect as it would reduce the complexity of computing on-cluster directly from the Clojure REPL.

However, I found a number of issues that would need to be addressed in order to support Spark Connect and Databricks:

- Problems with the default session.

- Problems with support for Databricks, although I suspect this is related to point 1.

Also, in general by my criteria the support classification is "support unknown":

- CI/CD build failing.

- Version 0.0.42 api docs broken, also affects version 0.0.41

- No commits since November 2023.

- No releases since November 2023.

- No PRs accepted or rejected since November 2023.

- No response when attempting to contact the author or maintainers.

Kafka Interop with Jackdaw

Jackdaw is the go-to library for Kafka interop. However, by my criteria the support classification is also "support unknown":

- No commits since August 2024.

- No releases since December 2023.

- No PRs accepted or rejected since August 2024. As a further example, here's a PR raised in May 2024 but not yet commented on either way by the maintainers.

Snowflake Interop with a New Clojure API!

Although the Snowpark library has Java and Scala bindings, it doesn't provide anything for Clojure. As such, it's currently not possible to interact with Snowflake using the Clojure way.

To address this gap, I decided to try my hand at creating a Clojure API for Snowflake as part of a broader effort to improve the overall situation regarding Clojure support for popular data tools.

The aim is to validate this approach as a foundation for enabling a wide range of data science or data engineering use cases from the Clojure REPL, in situations where Snowflake is the data warehouse of choice.

The README provides usage examples for all the current features, but I've copied the essential ones here to illustrate the API:

Load Clojure data from local and save to a Snowflake table

(require '[snowpark-clj.core :as sp])

;; Sample data

(def employee-data

[{:id 1 :name "Alice" :age 25 :department "Engineering" :salary 75000}

{:id 2 :name "Bob" :age 30 :department "Marketing" :salary 65000}

{:id 3 :name "Charlie" :age 35 :department "Engineering" :salary 80000}])

;; Create session and save data

(with-open [session (sp/create-session "snowflake.edn")]

(-> employee-data

(sp/create-dataframe session)

(sp/save-as-table "employees" :overwrite)))

Compute over Snowflake table(s) on-cluster and extract results locally

(with-open [session (sp/create-session "snowflake.edn")]

(let [table-df (sp/table session "employees")]

(-> table-df

(sp/filter (sp/gt (sp/col table-df :salary) (sp/lit 70000)))

(sp/select [:name :salary])

(sp/collect))))

;; => [{:name "Alice" :salary 75000} {:name "Charlie" :salary 80000}]

As an early-stage proof-of-concept, it only covers the essential parts of the underlying API without being too concerned with performance or completeness. Other more advanced features are noted and planned, pending further elaboration.

I hope you find it useful and I welcome any feedback or contributions!

Published: 2025-08-28

Tagged: dataengineering clojure spark datascience scicloj kafka flink snowflake

Scicloj on EdTech Platforms: Enabling Clojure-based Data Science in the Browser

You may or may not be aware that the Clojure data science stack a.k.a. Scicloj has been gaining momentum in recent years. To give a few highlights, dtype-next / fastmath are comparable with scipy / numpy for numerical work, and tech.ml.dataset / tablecloth are comparable with Pandas for tabular data. Kira McLean's 2023 Conj presentation explains that feature parity is almost upon us, and also offers some reasoning on why data scientists are now considering Clojure as an alternative to Python or R.

However, the leading EdTech platforms don't have much support for Clojure so all the potential benefits of both the language and Scicloj are not currently accessible to those communities.

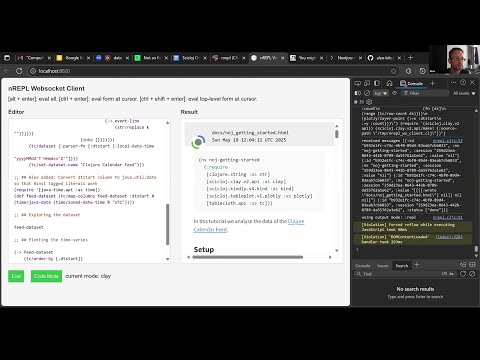

The good news is that I have created a proof-of-concept for using a browser to write, load and evaluate Clojure code running on a remote server using websockets, processing the results for display using the Scicloj notebook library clay.

I don't believe this combination has been achieved before. It is a significant step when you consider that Scicloj is Java/JVM-based on account of the underlying math support, there is no Javascript or ClojureScript implementation and that is likely to remain the case.

This work opens up the possibility for Clojure-based data science on e-learning platforms so that anyone anywhere can learn and experiment with the Scicloj stack.

Here are some examples of new e-learning content that could be unlocked..

Theory:

- Value vs state & functional programming

- Concurrent programming.

Clojure hands-on:

- Interactive programming and structural editing with the REPL

- Data processing with lazy sequences and transducers

- Data science notebooks covering stats, ML or LLM with rendered tabular data and charts.

More recently I gave an update on my progress at the Scicloj Visual Tools #34 meetup, including a live demo:

I hope you can appreciate the opportunity here. I'm happy to give a live demonstration to anyone who's interested!

Published: 2025-08-27

Tagged: clojure edtech datascience scicloj

What Time Is It? Understanding the Complexity of Data Streaming Tools

I argue that static documentation is insufficient to reason about the stateful operations of data streaming tools.

In a computer program, when values change over time we call this state. This is why we have two different words available to us for differentiating the context: the specific use of “state” instead of “value” signifies to the reader that we are intentionally composing two things, namely value and time.

Each of those concepts are simpler to reason about on their own, but when put together they require much more care. When you hear people saying “state is inherently complex”, this is what they are referring to. This is especially relevant when we are learning about data streaming tools as they need to consider state in many areas, and at scale: windowed aggregations, joins and other stateful operations, not to mention horizontal scaling, memory management through watermarks and checkpoints, fault tolerance and more.

So how best to understand the state management of these tools? Let’s take a look at what some of the most popular options provide to educate and inform users in this regard:

| Tool | Flink | Kafka Streams | Spark Structured Streaming | Storm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word count of reference docs | 20,042 | 45,492 | 19,908 | 28,682 |

| Informing users on stateful operations: t = written text d = diagrams & charts a = animations u = unit test facility s = simulator | t,d,u,s 1 | t,d,u | t,d,u | t,d,u |

| Execution plan checked against documented capabilities before running it? | Yes 2 | No 3 | Yes 4 | Yes 5 |

| If a simulator is available, where does it run? 1 = local 2 = browser + server / cloud 3 = browser only | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Based on the above, we can see that

- Despite their complexity, these tools are mostly limited to written documentation for educating and informing users on their stateful operations.

- While they all provide unit test facilities, these are intended to test your usage or composition of these operations rather than understanding the operations themselves. One could also argue that unit testing is targeting a later phase of your project than “educate and inform”.

- They are somewhat limited in any checks of their execution plans, and as a result things can slip through the cracks.

With that in mind, consider again that stateful data streaming problems necessarily involve the consideration of time, and as such they are fundamentally a dynamic concern. By contrast, written documentation is of course only static and for that reason I will submit that it is inefficient and inadequate for the intended purpose.

Indeed, I was affected by this issue personally when I ran into trouble with one of these tools. I still don't know if the problem I encountered is due to a misunderstanding of the (20,000 word) documentation or a bug.

So what’s the solution? Well, consider that we learn best by a combination of reading and doing rather than by reading alone. The “doing” is something that happens in real time, and one way to achieve this is by simulation.

In our case, I will define a simulation thus:

A means to observe the effects of a stateful operation, where for the same input as given to the production equivalent, the simulation will give the same output.

Given the stated purpose of a simulator in our case is to educate and inform, I will also add to the definition that it must require zero installation or setup. Further, to reduce costs and complexity it should also require minimal resources and ideally be fully serverless or standalone in operation. Finally, since the goal is to represent stateful operations, it should be capable of representing those in a visual dynamic by using animated forms for example.

I think there’s an opportunity for these tools (or new ones) to provide visual simulators as the primary means of reasoning for their stateful operations, and also as a complement to their existing documentation.

So with that out of the way, if we could build such a simulator what would it look like, how would it work and how could it be built? Here’s a motivational blueprint!

- Make the simulator available in a web browser.

- Write the core functions for the streaming solution and its stateful operations in a hosted language that compiles to code that can run in a browser. Then the same code can be used for both a production implementation and the browser-based simulation.

- Represent unbounded inputs using generators over lazy sequences.

- Define the execution plan specification and plan validation rules as data. Then, both the code that checks plans against the rules and any written reference guide can parse this same data, avoiding the possibility of inconsistencies.

- Within the simulator, represent stateful operations as declarative example-based or property-based BDD style given-when-then constructs, with an animated accumulation of results over time.

In conclusion, I hope you can appreciate the benefits that simulations would bring in this space, and I also hope to have suitably motivated other people in the community to take the baton!

Credits.

Igor Garcia for your feedback and advice: thank you 🙏

- Flink provides an operations playground but it doesn’t specifically cover stateful operations. There’s also a worked example based on fraud detection, but the explanations are 100% written.↩

- Flink performs semantic checks for jobs defined using the Table API and SQL. However, the pre-execution validation is not exhaustive, and certain subtle errors or issues might only manifest as unexpected behavior or silent failures during runtime.↩

- Kafka Streams doesn’t have a distinct pre-execution validation phase in the traditional sense. Instead it relies on a combination of static type checking and the TopologyTestDriver as part of a unit testing strategy.↩

- Spark Structured Streaming has a multi-layered validation process to ensure correctness and feasibility of computations before their execution. The UnsupportedOperationChecker enforces streaming-specific rules during the logical planning stage.↩

- Apache Storm's pre-execution topology checks focus on structural and configuration validity, and exceptions are thrown to indicate structural problems, configuration errors and authorization failures. Although it provides facilities for programmatically defining and inspecting topology structure and configuration, a dedicated validation API against documented capabilities is absent.↩

Published: 2025-05-28